Nadsat has had a curiously rich afterlife beyond Anthony Burgess’s novella and Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation. Its penetration of popular music culture in particular has been profound. Numerous bands have named themselves after phrases from the text, and many more have cited Nadsat phrases in their songs and lyrics.

Read moreRiddley, Max, Iain and Dave: Riddley Walker’s linguistic legacies

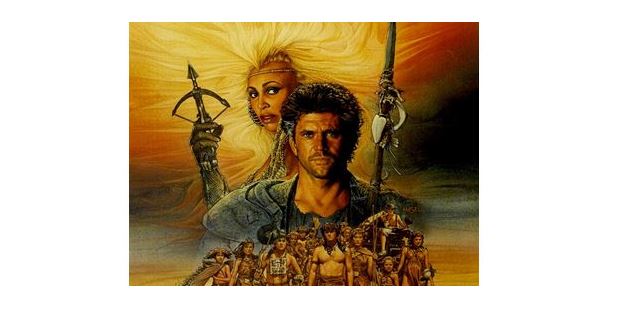

How do we get from Riddley Walker to children rescuing Mel Gibson in the outback, or a reincarnation castle on a future doomed Earth, or even an outraged London cabbie who becomes an accidental prophet? By language, or rather, by the particular creative distortions thereof which Russell Hoban innovated in his novel.

Before continuing, readers may be interested in we should mention a Riddley Walker event tomorrow – Tiny manyings for Riddley presented as part of the Kent Open Thinking Programme and is supported by Canterbury Festival and The Gulbenkian.

Read more“The Sylents Swallering Up the Souns” – Riddley Walker and the critics

Okay, so we lied. There are actually going to be four posts in this series. In the previous two, we looked at how Anthony Burgess, author of A Clockwork Orange (which is often proposed as an influence on Riddley Walker) praised Russell Hoban’s 1980 novel, and also some of the literary elements which went into the creation of ‘Riddleyspeak’.

In this article, we’re going to look at Riddleyspeak itself, how it functions linguistically and what the critics made of it. In the next and final one, we’ll take a look at Riddley’s legacy.

Read more