As we mentioned a week or so ago, we’re delighted to have a new chapter out in Matt Melia and Georgina Ogilvy’s edited collection Stanley Kubrick, Anthony Burgess and A Clockwork Orange. Our study looks at what happened to Nadsat in Kubrick’s adaptation of ACO, which came out in 1971. How did it survive in this process, bearing in mind Burgess wasn’t really involved in it? Did Kubrick take any liberties?

First a bit of background [incidentally, Filippo Ulivieri gives a fascinating account of the Burgess-Kubrick relationship as it developed from the film’s conception through to its reception and subsequent events (Chapter 1 of Stanley Kubrick, Anthony Burgess and A Clockwork Orange)]. As it happens, Kubrick wasn’t the first person to be drawn to adapting ACO for the screen. The Rolling Stones were at one point interested – as outlined in an earlier post – and Andy Warhol loosely adapted it as Vinyl in 1965. But Kubrick’s was the first serious attempt at taking on the book.

Burgess wasn’t involved in the making of the film but was happy to participate in promotional activities, pronouncing himself (at the time) very happy with the way Kubrick had handled the book. This initial enthusiasm later dulled due to controversies over the violence in the film and over whether it contributed to so-called copy-cat attacks. Burgess also felt the notoriety surrounding ACO overshadowed his other (often superior) literary output and that Kubrick’s retirement from the fracas over the film left him more open to attack. But, as Ulivieri points out, Burgess’s attitude towards both film and book was inconsistent and, like with much else in his life, his public pronouncements on this topic shouldn’t always be relied on.

Nadsat in the film

When we first conceived of this study, we were intrigued by what the famous film critic Pauline Kael had to say about the film adaptation:

The book is a fast read; Burgess, a composer turned novelist, has an ebullient, musical sense of language, and you pick up the meanings of the strange words as the prose rhythms speed you along.

The movie retains a little of the slangy Nadsat but none of the fast rhythms of Burgess’s prose, and so the dialect seems much more arch than it does in the book. Many of the dialogue sequences go on and on, into a stupor of inactivity.

Pauline Kael’s review of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (“A Clockwork Orange: Stanley Strangelove”) in The New Yorker, January 1, 1972

Kael’s claim that ‘a little’ Nadsat remains in the film contrasts somewhat with Burgess’s own assessment that the film ‘kept 75% of the Nadsat’ (as reported in the Evening Standard – Ulivieri). So what is the true figure, ‘a little’ or ‘75%’, or something else? And 75% in what sense – of the range of words (types) or Nadsat as a proportion of the whole text? Burgess’s estimate seems unrealistic – keeping that much Nadsat would make it impossible, surely, for viewers to understand parts of the film. On the other hand, for anyone who has watched the film, Kael’s claim that only a little Nadsat remains also seems wrong even if, as she seems to suggest, Nadsat does seem to have retreated from its central position in the book to a role of contributing to the overall style of the film.

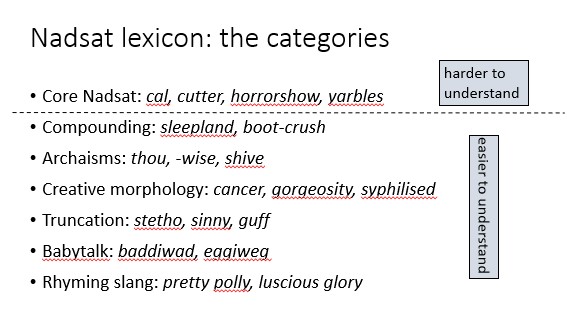

In order to get an idea of how Nadsat was used in the film, we need a reminder of the different categories of this anti-language (see also here). They are shown below with some examples. The key thing to remember here is that ‘Core Nadsat’ items are those that are mainly based on Russian and will therefore initially likely be unclear to most viewers, whereas words in other categories are typically more immediately comprehensible. If the script for Kubrick’s film truly contained 75% of the original Core Nadsat list, the film would have been very difficult to understand.

So what does actually happen to Nadsat in the film? Using the categorisation above, what we found was quite a clever adaptation of the anti-language to this new mode. We can see how this was achieved in a number of ways. Firstly, just looking at lexicon size, Nadsat in the film contains a much smaller set of words – 88 in total compared to 355 items in the book (so not 75%!); the proportion of Core Nadsat words in both cases is similar (around 60%). This makes sense, not least since the film is far shorter in numbers of words (five times shorter, in fact). It still seems quite a lot of new words to include in a film (50+ Core Nadsat items).

But this is only one part of the picture. We need to know if the concentration of Nadsat remains the same – does one meet Nadsat words as often in the film as in the book? The answer is that Nadsat is much less concentrated in the film. Obviously, viewers wouldn’t be able to handle too much Nadsat in one go – or at least not too much Core Nadsat. That’s no doubt why we see a dramatic difference between book and film in this category in particular, whereas in the other, easier to understand categories, there is even sometimes a rise in occurrences, relatively speaking. So, for Archaism, what, then, didst thou in thy mind have? is retained wholesale from the book. This sort of retention may have led Kael to find the film more ‘arch’ than the book.

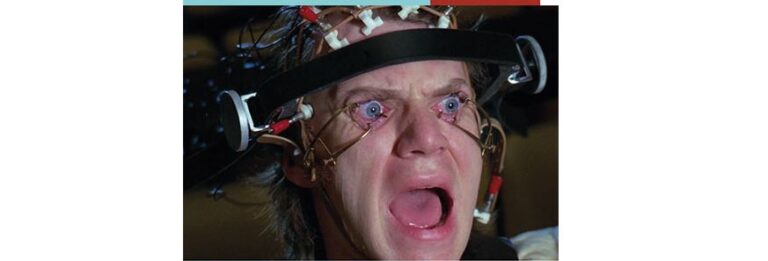

Interestingly, too, our examination of the script threw up two ‘new’ Nadsat words both of which comply with Nadsat word formation rules. The first is steakiweaks – compare this with e.g. eggiwegs, jammiwam – and the second is lidlocks, the contraptions used to prevent Alex from closing his eyes (cf afterlunch, boot-crush)

Overall, then, this indicates that Kubrick and his screenwriters took the adaptation of Nadsat for the film seriously and they seem to have taken a sensible approach to ensure that its impact can be felt without overwhelming the viewer – after all there is plenty else to overwhelm the viewer in the film already!

For more on this please read our chapter – available at all good bookstores…

Till next time droogies!

One thought on “Nadsat on screen – Burgess vs. Kubrick”